WHO IS DRAVIDIAN? –A GENOMIC-ARCHAEOLOGICAL REASSESSMENT.

ABSTRACT

This study presents a genomically anchored model identifying the Dravidians as an indigenous population of peninsular India with ancestry extending to the 2.5-million-year prehistoric continuum documented at Attirampakkam. The research integrates archaeological sequences, ancient DNA (aDNA), and modern population genomics to propose that early South Indian AASI (Ancient Ancestral South Indian) populations represent the foundational layer of Proto-Dravidian ancestry. During the Mesolithic period, segments of these AASI-derived groups migrated northward into the Indus basin, where they admixed with pre–Indo-European Iranian-related Neolithic agriculturalists who expanded eastward from the Zagros region between 7000 and 5000 BCE. This long-term admixture produced the characteristic genetic profile of the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), defined by Iranian-related and AASI ancestry with no Steppe input.

The Rakhigarhi aDNA sample currently the only genome from a Harappan core settlement—exhibits ~70–80% Iranian-related Neolithic ancestry and ~20–30% AASI ancestry, lacking Steppe markers. This study interprets the Rakhigarhi genome as representing the Iranian-leaning pole of an already mixed Harappan genetic cline, rather than evidence for an Iranian origin of the Harappans. Comparative analysis with Indus Periphery genomes from Shahr-i-Sokhta and BMAC confirms substantial variability in AASI–Iranian ancestry proportions across the Indus cultural world. Following the arrival of Steppe pastoralists (~2000 BCE), Harappan-descended populations underwent demographic fragmentation. This paper proposes a bifurcated dispersal: one branch migrating westward toward the Iranian plateau, potentially underpinning linguistic parallels associated with the Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis; and another returning southward to peninsular India, forming the ancestral population from which the Dravidian language family diversified. Genomic continuity observed in modern South Indian tribal groups (Irula, Paniya, Kurumba), including high AASI ancestry and deep-rooted mitochondrial haplogroups (U2, U7), supports this reconstruction and demonstrates genetic continuity from prehistoric AASI ancestry through the IVC to contemporary Dravidian-speaking populations. This research contributes to broader discussions on South Asian population history by offering an integrated archaeological-genomic model positioning the Dravidians as one of the world’s longest continuous bio-cultural lineages—originating in South India, participating centrally in the formation of the Indus Valley Civilization, and later dispersing across Iran and the southern peninsula through multi-layered demographic interactions.

INTRODUCTION

Who is Dravidian?

The question “Who is Dravidian?” remains central to both contemporary discourse and long-term historiography. In Tamil Nadu, the term has gathered immense political, cultural, and academic importance. Yet despite its prominence, the deeper origins of Dravidian identity remain contested. Based on the research done by this author, Dravidian identity arises through a convergence of three inseparable elements geographical rootedness, ancestral continuity, and linguistic evolution. When examined through archaeology, prehistory, and modern genomic research, this triad reveals Dravidians as one of the oldest continuous human populations in the world, shaped by movements and interactions that predate recorded history.

DEEP PREHISTORIC ROOTS: ATTIRAMPAKKAM AS THE FOUNDATION

Any discussion of Dravidian origins must begin with the extraordinary archaeological site of Attirampakkam in Tamil Nadu. With evidence of hominin occupation stretching back nearly 2.5 million years, Attirampakkam provides a rare window into long-term human continuity. The Acheulean, Middle Paleolithic, and Mesolithic assemblages of this region demonstrate cultural persistence that is unparalleled elsewhere in South Asia.

This deep-time occupation aligns with the genetic ancestry known today as the Ancient Ancestral South Indians (AASI). Modern genomic studies confirm that AASI ancestry survives most strongly among tribal communities in South India and Sri Lanka and this suggests a direct line of descent from early southern Stone Age populations to the modern groups who preserve the oldest genetic signals in the subcontinent particularly the Irulas and Veddas.

The idea that these ancient populations formed the biological base of the Dravidian peoples aligns well with emerging anthropological models. Although the linguistic term “Dravidian” cannot be applied to Paleolithic groups, the continuity of population presence, culture, and genetics indicates a long-term ancestral link.

Mesolithic Expansion and Movements toward the Indus Valley

>The next major phase in Dravidian Ethnogenesis occurred during the Mesolithic period, when significant groups from peninsular India began migrating northward. These movements were facilitated by riverine corridors, coastal routes, and expanding ecological opportunities. Archaeologically, Mesolithic sites across India show striking similarities in microlithic technologies. This widespread distribution reflects mobility and interaction networks that connected South India with western India and the northwestern subcontinent and this movement planted the seeds of demographic and cultural contributions to the later Indus Valley Civilization (IVC). Genomic evidence strengthens this interpretation. Among modern populations, the closest match to this IVC profile is found among South Indian tribal groups especially the Irulas. This demonstrates that the ancestors of present-day Dravidians were not outsiders to the Indus world but formed a significant component of its population

Civilizational Flourishing and Historical Encounters

Today’s research acknowledges that the Indus Valley Civilization represents an era when the ancestors of Dravidian peoples participated in one of the world’s earliest urban cultures. The sophistication of Harappan city planning, trade networks, agriculture, and craft specialization reflects a mature and stable society.

However, around 2000–1500 BCE, new groups Indo-European steppe nomads entered the northwest of the subcontinent. Their arrival introduced fresh cultural and linguistic dynamics and this encounter marked a turning point in Dravidian population movements. Interactions between the Harappans and incoming steppe groups ranged from conflict to gradual cultural integration. As Indo-European influence expanded in the north, sections of the Indus-linked population dispersed in different directions.

One group, moved toward the Iranian plateau. Their interaction with local populations contributed to the formation of a cultural and linguistic zone that scholars today call the

Elamo-Dravidian sphere. The structural parallels between Elamite and Dravidian languages lend weight to this connection, though the question remains open to scholarly debate.

Another group returned southward into peninsular India, blending with Indo-European groups yet retaining their original ancestral core. This southern branch became the root of the Dravidian-speaking populations known today.

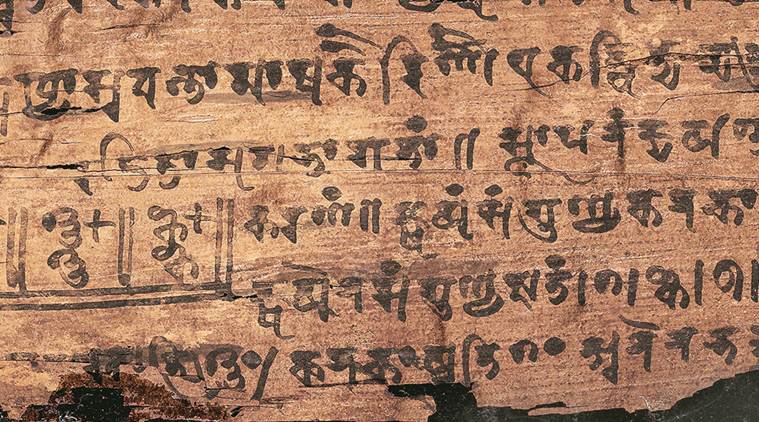

The Emergence and Evolution of Dravidian Languages

When these returning groups resettled in South India after the decline of the IVC, they carried with them the foundations of a linguistic tradition that would become Proto-Dravidian. This ancestral language evolved under the influence of both ancient South Indian tongues and the linguistic memory of the Indus regions. Over time, Proto-Dravidian diversified into major branches:

- Tamil — the oldest and most conservative

- Telugu — evolved further north and east

- Kannada — emerging from proto-Telugu regions

- Malayalam — diverging from Tamil in the early medieval period

This linguistic unfolding aligns with archaeological evidence of Iron Age and early historic settlements across the peninsula.

The Genetic Anchor: Irulas, Veddas, and Continuity

The most important aspect of this research is that the strongest evidence for a deep Dravidian ancestry comes from the genetic profiles of the Irulas of Tamil Nadu and Kerala, and the Veddas of Sri Lanka. Genomic studies show that these groups carry:

• High proportions of AASI ancestry

• Deep mitochondrial haplogroups, especially U

• Strong affinity to the Rakhigarhi Harappan genome

Their shared heritage can also be explained by the geological fact that Sri Lanka and South India were connected until around 8000 BCE. This land link enabled free movement of Stone Age communities. Based on the research done by this writer that the Belilena Cave ( also can be added Balangonda Man with Fa-hienlena Cave ) cave dwellers of Sri Lanka, the Veddas, and the Irulas are genealogical extensions of the same ancient population.

This triad of evidence archaeology, genetics, and geography forms the backbone of the theory that Dravidian identity represents one of the world’s oldest continuous human lineages.

Dravidians as Location, Lineage, and Language

ravidians possess a three-dimensional identity:

A Distinct Geographical Homeland.

South India and Sri Lanka form the earliest and most enduring Dravidian landscape.

A Distinctive Genetic Continuity.

Dravidian-speaking populations share a recognizable genetic pattern shaped by AASI and IVC ancestry.

A Distinct Linguistic Tradition.

The Dravidian languages collectively form one of the world’s oldest language families still in use.

Combined, these aspects demonstrate that the Dravidians are not a recent political or ideological construct but a civilizational formation rooted in deep prehistory.

Conclusion

According to the present study, the Dravidian identity emerges from a unique confluence of deep-time human presence, archaeological continuity, genetic inheritance, and linguistic evolution. From the ancient toolmakers of Attirampakkam to the urban planners of the Indus civilization, from movements into the Iranian plateau to the re-establishment of powerful kingdoms in South India, the Dravidian story spans millions of years of human history. This long arc positions the Dravidians not merely as a linguistic or regional group but as a lineage with profound historical, cultural, and biological depth.

Appendix 1: The Rakhigarhi Genome in Context

Introduction

The discovery and genomic sequencing of the Rakhigarhi woman currently the only ancient DNA recovered from the core region of the Indus Valley Civilization—has raised important questions about how this individual fits within broader theories of Dravidian origins. As argued in this paper, the Dravidians originated in peninsular India, migrated northward into the Indus Valley during the Mesolithic period, developed an advanced civilization over several millennia, and later divided into two branches: one moving westward toward the Iranian plateau and the other returning to South India. To refine this model, it is necessary to understand where the Rakhigarhi genome belongs within Dravidian ethnogenesis.

A MODEL OF TWO-PHASE DRAVIDIAN INTERACTION

>

Phase 1: AASI-derived groups migrate from peninsular India toward the Indus region, merging with

Iranian-related Neolithic populations already present there. This merger produced a genetically diverse Harappan population.

Phase 2:After the arrival of Indo-European nomads (2000–1500 BCE), Harappan groups dispersed:

• One branch moved westward toward Iran, contributing to the Elamo-Dravidian linguistic zone.

• Another branch returned to peninsular India, forming the nucleus of early Dravidian-speaking societies.

Under this model, the Rakhigarhi sample belongs to the mixed population of Phase 1. Her Iranian-related ancestry represents one end of a population continuum and not the sole defining ancestry of the Harappans.

The Rakhigarhi woman most plausibly represents an Iranian-leaning Harappan subgroup within this mixed population.

WHY THE RAKHIGARHI SAMPLE DOES NOT INVALIDATE THE THEORY ?

According to this author, there are three logical reasons why the Rakhigarhi sample fits comfortably within my larger Dravidian-origin thesis:

A SINGLE SAMPLE IS NOT REPRESENTATIVE

One individual cannot reflect the full heterogeneity of a civilization spanning 1 million sq. km. and 700+ sites. More genomes are required to form a complete picture.

SHE REPRESENTS A SPECIFIC

SUBGROUP The Rakhigarhi woman may belong to:

A later Harappan subgroup with higher Iranian-related ancestry

A local community that experienced greater western interactions

A mixed lineage reflecting long-term demographic blending

Her presence does not negate the existence of AASI-rich Harappan groups more closely aligned with South Indian ancestry.

3. THE HARAPPAN POPULATION WAS INTERNALLY DIVERSE

As Moorjani (2013) and Narasimhan et al. (2019) affirm, South Asians have always been genetically varied. Polarized samples (high AASI or high Iranian ancestry) are expected within such a large civilization."The Rakhigarhi genome reflects the internal diversity of the Harappan population. According to me, she represents the Iranian-leaning end of the Harappan genetic spectrum, formed through long-term interactions between AASI-derived Proto-Dravidian migrants from peninsular India and early Iranian-related agricultural groups who settled in the region millennia earlier. This interpretation integrates the Rakhigarhi data seamlessly into my South Indian-origin model, without contradicting the broader Dravidian migration framework.

CONCLUSION.

The Rakhigarhi woman stands not as a challenge but as a complementary piece in understanding

Dravidian origins. Her genome provides evidence of the genetic complexity of the Indus Valley Civilization and highlights the interplay between Iranian-related and South Indian ancestries. According to me, the Rakhigarhi sample validates the broader narrative that the Harappans were a mosaic population shaped by interactions across South Asia and the Iranian plateau. This diversity is entirely consistent with a peninsular Indian origin of Proto-Dravidians, followed by migration, settlement, cultural development, admixture, and later dispersal.

Appendix 2: Preserving Skeletal Evidence

Understanding the origins, evolution, and identity of the Dravidian people requires not only theoretical synthesis but also a firm foundation in scientific evidence and the most crucial material for reconstructing Dravidian history is skeletal remains excavated from prehistoric and historic sites across Tamil Nadu and the wider Dravidian landscape. These remains form the biological archive through which we explore population history, migration patterns, genetic affinities, cranial morphology, dietary habits, health systems, and ancient cultural practices. Without them, the scientific exploration of Dravidian identity remains incomplete.

Yet, the story of skeletal preservation in Tamil Nadu is one of deep concern. Thousands of remains recovered from megalithic sites—especially from urn burials, cist burials, cairn circles, and pit burials—have not been preserved with the care they deserve. Many were discarded, poorly stored, or left unidentified. This has resulted in a serious scientific loss, depriving researchers of the most direct evidence of early Dravidian populations.

Among all sites, Adichanallur stands out as a symbol of what was lost and what could still be regained. Often described by scholars as the "Cradle of Tamil Civilization," Adichanallur yielded one of the largest collections of ancient skeletal remains and burial urns in South Asia. These remains could have revolutionized our understanding of ancient Tamil society—its lineage, cultural complexity, genetic profile, and continuity. Scholars have repeatedly noted that Adichanallur should have been maintained with far greater care, especially given its extraordinary antiquity and global significance, and the lessons from Adichanallur reflect the urgent need for a systematic preservation strategy.

Preservation becomes even more crucial when we consider tribal zones, where some of the most ancient genetic signatures of the Dravidian population survive. Populations such as the Irulas, Paniyas, Todas, Kotas, and the Veddas of Sri Lanka represent living links to the earliest inhabitants of South India. Skeletal remains excavated from these regions hold immense value—not only for reconstructing their ancestry but also for understanding the shared biological heritage of all Dravidian-speaking communities and the preservation of tribal-zone remains must be treated as a top priority in future research planning.

In this context, the present writer welcomes the initiative of the Tamil Nadu Government, which in 2025 launched the "Tholkudi Project," a Tribal Studies and Welfare Scheme aimed at the digital documentation and research on tribal communities. The Tholkudi Project, with its focus on cultural preservation, anthropological archives, and digital heritage, marks a significant step forward. According to me, if implemented rigorously and supported by academic institutions, it can transform how we safeguard the physical and cultural heritage of tribal populations who form the deepest genetic and cultural layers of Dravidian identity.

However, preservation alone is not enough. There is an acute shortage of trained scholars in two essential fields:

Physical Anthropology for studying skeletal morphology, age, sex, pathology, trauma, and population characteristics.

Genetic Science / Archaeogenomics for extracting and interpreting ancient DNA (aDNA), the most powerful tool in reconstructing early Dravidian ancestry.

Thus, Tamil Nadu urgently needs more students, researchers, and professionals trained in these disciplines. Without them, even well-preserved remains will lie unstudied, and opportunities to understand our past will be lost. Universities must develop new programs in Physical Anthropology, Human Genetics, Bio-archaeology, and Ancient DNA Research. Museums and archaeological departments need to collaborate with genomic laboratories to carry out world-class research.

In conclusion, if we are to uncover the full story of "Who is Dravidian?", we must begin by safeguarding the physical evidence left by our ancestors. The skeletal remains beneath our soil are not mute objects; they are the silent custodians of our past and preserving them with dignity, studying them systematically, and training new generations of scholars to analyze them is not only a scientific duty but a cultural responsibility. From Adichanallur to tribal heartlands, from megalithic burials to modern genomic laboratories, the future of Dravidian research depends on our commitment to protect and study the biological heritage that connects us to our deepest roots.

REFERENCES

1. Shinde, V. et al. “An Ancient Harappan Genome from Rakhigarhi.” Cell (2021).

2. Lazaridis, I. et al. “Genomic Insights into the Origins of Farming in the Ancient Near East.” Nature(2016).

3. Narasimhan, V. et al. “The Formation of Human Populations in South and Central Asia.” Science(2019).

4. McAlpin, D. “Elamite and Dravidian: Evidence for a Genetic Relationship.” Current Anthropology.

Appendix 3: Scientific Dating of Attirampakkam Tools

The prehistoric site of Attirampakkam in Tamil Nadu is one of the most significant Stone Age sites in South Asia, providing a continuous archaeological sequence from the early Acheulian to the Middle Palaeolithic. Scientific dating performed over the past two decades has helped establish a robust chronology for the stone tool assemblages found at the site. The earliest Acheulian levels were dated using cosmogenic nuclide burial dating and palaeomagnetic analysis. These methods demonstrated that Acheulian hominins were present no later than approximately 1.07 million years ago (Ma). A pooled burial age estimate places the earliest Acheulian tool horizon at around 1.51 ± 0.07 Ma, making Attirampakkam one of the oldest Acheulian sites in the subcontinent.

A subsequent technological transition at Attirampakkam marks the emergence of Middle Palaeolithic flake technologies, including Levallois reduction methods. These deposits were dated using post–infrared infrared stimulated luminescence (pIR-IRSL), which measures the last exposure of sediments to sunlight. The dating showed that the Middle Palaeolithic began around 385 ± 64 thousand years ago (ka) and continued until approximately 172 ka. These dates are crucial for understanding the evolution of hominin behaviour in India and suggest that Middle Palaeolithic technologies emerged in South Asia independently or as part of a broader regional pattern.

The combination of burial dating, luminescence methods, and stratigraphic analysis confirms that Attirampakkam preserves an unparalleled chronological sequence. This record captures the long-term technological transitions of early hominins, offering valuable insights into the timing and nature of Acheulian persistence, the shift toward Levallois technologies, and the deep antiquity of human occupation in the region. The findings have reshaped broader models of human dispersal, especially regarding early hominin movements across the Indian subcontinent.

REFERENCES

Pappu, S., Gunnell, Y., Taieb, M., Brugal, J.-P., et al. 2011. “Early Pleistocene Presence of Acheulian Hominins in South India.” Science 331(6024): 1596–1599.

Akhilesh, K., Pappu, S., Rajapara, H. M., Gunnell, Y., et al. 2018. “Early Middle Palaeolithic Culture in India Around 385–172 ka Reframes Out of Africa Models.” Nature 554: 97–101.

Pappu, S., Gunnell, Y., Brugal, J.-P., Taieb, M., et al. 2003. “Excavations at the Palaeolithic Site of Attirampakkam, South India.” Antiquity 77(297): 687–697.

“Attirampakkam.” Encyclopaedic summary including dating methods and stratigraphic description.

Appendix 4: Limits of Skeletal ‘Race’ Typology

The question of whether “racial features” can be identified from excavated skeletons has a long and complex history. Early anthropologists attempted to classify skeletal remains into racial types using cranial measurements, nasal indices, and other morphometric traits. However, modern biological anthropology has demonstrated that such traits vary gradually across populations, do not form discrete racial units, and are easily influenced by environmental and developmental factors. As a result, contemporary scholarship treats “race” as a cultural–historical category rather than a biological one, and skeletal analysis today focuses on estimating broad ancestry rather than identifying fixed racial types.

In the South Asian context, earlier studies on sites such as Adichanallur applied outdated racial typologies—sometimes describing skulls as “Australoid,” “Mediterranean,” or “early Dravidian.” These conclusions are now recognized as speculative and unsupported, derived from outdated models of racial classification. Modern reviews emphasize that skeletal series from South India are heterogeneous and cannot be used to define a singular “Dravidian race.” Instead, they reflect the long-term population diversity of the region. New efforts to extract ancient DNA from these skeletons have had limited success so far, due to poor preservation, but they underscore a shift away from racial typology toward genomic analysis.

Ancient DNA research—especially studies from the Indus Civilization, the Iranian Plateau, the Bactria–Margiana region, and early historic South Asia—has revealed that populations across the subcontinent were formed through mixtures of Iranian-related agricultural ancestry, indigenous South Asian hunter-gatherer ancestry (ASI), and later Steppe-related ancestry. Many South Indian and Sri Lankan groups today retain high proportions of ASI-related ancestry, and tribal communities such as the Irula, Kurumba, Palliyar, and Veddas preserve deep regional genetic signatures. Yet none of these components corresponds uniquely to a “Dravidian race.” Rather, they represent genetic strata that may have contributed to the communities who eventually came to speak Dravidian languages.

In summary, while skeletal remains—especially when combined with ancient DNA—can illuminate ancestry, migration, and population history, they cannot scientifically identify a distinct “Dravidian racial type.” The most accurate framing is that certain ancient ancestry components, particularly those combining Indus-periphery and ASI lineages, contributed significantly to the populations of southern India and Sri Lanka. These biological histories can be studied alongside linguistic and archaeological evidence, but they do not map neatly onto historical concepts of race. Modern research therefore focuses on ancestry, population structure, and cultural evolution rather than attempts to define any racial identity from skeletons.

Appendix 5: Were the Indo-Europeans Indigenous?

INTRODUCTION

The question of whether Indo-Europeans entered India from outside or emerged indigenously within the subcontinent has long occupied archaeologists, linguists, and historians. Modern political debates have intensified this discussion. This article evaluates archaeological, linguistic, historical, and genomic evidence to determine whether the Indo-Europeans were indigenous to India or entered from the northwest during the early second millennium BCE.

LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE FOR INDO-EUROPEAN MIGRATION

Comparative linguistics demonstrates that Sanskrit belongs to the wider Indo-European family, sharing cognates with Greek, Latin, Avestan, and Germanic languages.1 Examples such as pitar/pater, madhu/mead, and asura/ahura indicate a shared proto-language. Vedic Sanskrit and Avestan share deep grammatical parallels, reflecting Indo-Iranian unity before separation.2 The geographic spread of Indo-European languages from Ireland to India requires migrations from a homeland, with the Pontic–Caspian Steppe being the most supported.3

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Indo-European cultural markers—horse-centered mobility, spoked-wheel chariots, and kurgan burials—are absent in Mature Harappan India (2600–1900 BCE) but appear after 1800–1500 BCE.4 True domesticated horses are rare in Harappan layers, and clear remains appear only after the Harappan decline.5 The Gandhara Grave Culture (Swat Valley, 1800–1200 BCE) shows Central Asian traits and Steppe ancestry, suggesting intrusive populations.6

GENOMIC EVIDENCE

Ancient DNA studies confirm Steppe ancestry entered India around 2000–1500 BCE and was absent in Harappan genomes such as Rakhigarhi.7 Y-chromosome lineage R1a-Z93, linked to Indo-Iranian expansions, is common in North India but absent in Harappans, supporting migration from the Steppe.8

HISTORICAL AND TEXTUAL EVIDENCE

The Rig Veda’s geography focuses on Punjab–Afghanistan (Saraswati, Sindhu, Kubha, Sarayu). The Ganga appears only once and very late.9 Early hymns describe conflicts between Indo-Aryan tribes and fortified Dasa/Dasyu populations, potentially reflecting interactions with post-Harappan groups.10

EVALUATING THE INDIGENOUS ARYAN HYPOTHESIS

The “Indigenous Aryan” model claims Sanskrit and Indo-European languages originated in India and spread outward. However, Sanskrit is not the

proto-language—linguistics shows it is a daughter branch.11 Genomics shows Steppe

ancestry entering India after 2000 BCE.12 Archaeology shows chariots, horses, and Steppe artefacts only after the Harappan collapse.13 Textual geography situates early Vedic culture in the northwest.14 The Indigenous Aryan theory survives mostly for political or ideological reasons, not evidence.

CONCLUSION

Combined evidence from linguistics, archaeology, textual studies, and genomics strongly supports that Indo-Europeans entered India from the northwest during 2000–1500 BCE, gradually integrating with local post-Harappan groups. This was not an invasion but a series of migrations. Indigenous Dravidian populations formed the Harappan base, while Indo-Europeans merged into the evolving cultural fabric later.