The Sharada Zero: Has India’s Greatest Mathematical Discovery Been Misdated ?-Need of Fresh Carbon -14 dating.

By T.K.V.Rajan, Archaeologist and Editor, Indian Science Monitor.

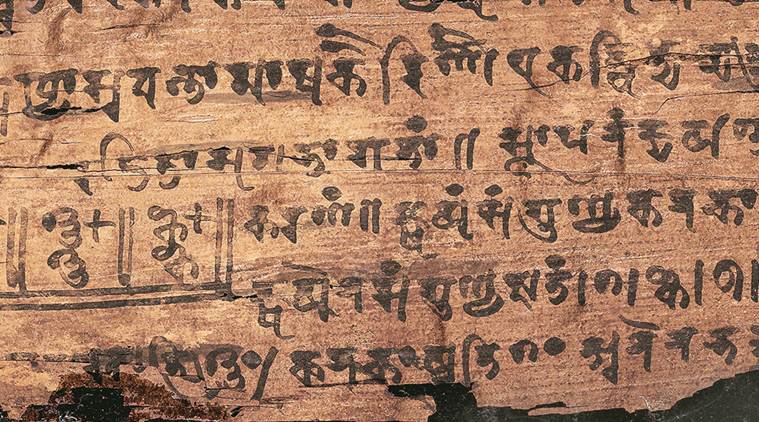

The Bakhshali manuscript, written in the ancient Sharada script and containing some of the earliest known uses of the numeral zero, occupies a uniquely important place in the intellectual history of India.

As a mathematical document, it represents the sophisticated computational traditions that flourished in the subcontinent long before the European Renaissance. Its treatment of arithmetic, algebra, extraction of roots, and especially its use of the Sunya Bindu (the dot representing zero), demonstrates that ancient India possessed an advanced understanding of positional notation and numerical abstraction. For this reason, the manuscript has always been regarded as a crucial witness in the global history of mathematics.

A significant portion of its scholarly value comes from the question of its date. In 2017, when the Bodleian Library in Oxford released the results of Carbon-14 dating for three folios of the manuscript, the findings appeared revolutionary. One of the folios was dated to approximately 300 BCE, prompting international headlines claiming that the manuscript contained the world’s oldest written zero. However, this early dating was immediately questioned by a group of mathematicians, Indologists, and historians of science. They pointed out that the manuscript was stylistically and linguistically inconsistent with such an early date. Moreover, the three dated folios spanned nearly seven centuries, from the early centuries BCE to almost 1000 CE, raising questions about the reliability of the sampling process. These scholars insisted on a more cautious and methodologically sound approach, arguing that the manuscript was likely composite, copied over different periods, or contaminated in ways that carbon samples had not fully accounted for.

In 2024, a revised and more conservative dating was released, placing the entire manuscript between 800 CE and 1100 CE. This dramatically altered the earlier narrative, shifting the Bakhshali manuscript from the early centuries BCE to the medieval period. As an archaeologist, however, I find this shift in dating deeply thought-provoking. In recent decades, a number of archaeological discoveries across India have been subjected to dating inconsistencies and politically influenced interpretations. In several cases, established dates have been challenged, altered, or dismissed not purely on scientific grounds but due to ideological pressures or institutional conservatism.

The archaeological discipline, which should ideally remain free from politics, has often found itself entangled in debates where science is overshadowed by competing cultural narratives. Such trends have created an atmosphere of uncertainty about the integrity of dating results, especially when broad civilizational questions hinge upon them. It is within this context that the dating of the Bakhshali manuscript must be viewed critically. The shift from 300 BCE to 800 CE is not a minor correction but a transformation of more than a millennium. Whether the early date was genuinely flawed or whether the later re-dating leaned toward excessive caution remains an open question. What is certain is that both dates cannot simultaneously be correct, and the current scholarly environment demands greater transparency and more rigorous methodology.

Given the manuscript’s global importance not only as an Indian document but as a cornerstone of world mathematical history its dating must be beyond dispute. For these reasons, I am requesting that the Government of India formally approach the British Library and the Bodleian Library to permit a fresh round of carbon dating under a joint scientific advisory committee. This committee must include experts in paleography, manuscript conservation, radiocarbon science, Indian mathematical history, and archaeological chronology. Only a fully transparent, multi-institutional, and peer-reviewed re-evaluation of the manuscript’s physical age can settle the debate. Such a request is not merely academic; it is a matter of preserving the authenticity of India’s scientific heritage. The Bakhshali manuscript is not only an artifact—it is an intellectual monument. It represents the brilliance of early Indian mathematicians who conceived, understood, and operationalized the symbol zero in ways that later transformed global science. To reconstruct the genuine history of ancient India, we must ensure that evidence of this magnitude is evaluated with utmost care, free from political influence, and grounded in the highest standards of scientific inquiry. A fresh dating of the manuscript is therefore not only justified but necessary. It is essential for restoring confidence in the chronology of India’s intellectual achievements and for presenting an accurate, scientifically validated narrative of the ancient past.

A significant portion of its scholarly value comes from the question of its date. In 2017, when the Bodleian Library in Oxford released the results of Carbon-14 dating for three folios of the manuscript, the findings appeared revolutionary. One of the folios was dated to approximately 300 BCE, prompting international headlines claiming that the manuscript contained the world’s oldest written zero. However, this early dating was immediately questioned by a group of mathematicians, Indologists, and historians of science. They pointed out that the manuscript was stylistically and linguistically inconsistent with such an early date. Moreover, the three dated folios spanned nearly seven centuries, from the early centuries BCE to almost 1000 CE, raising questions about the reliability of the sampling process. These scholars insisted on a more cautious and methodologically sound approach, arguing that the manuscript was likely composite, copied over different periods, or contaminated in ways that carbon samples had not fully accounted for.

In 2024, a revised and more conservative dating was released, placing the entire manuscript between 800 CE and 1100 CE. This dramatically altered the earlier narrative, shifting the Bakhshali manuscript from the early centuries BCE to the medieval period. As an archaeologist, however, I find this shift in dating deeply thought-provoking. In recent decades, a number of archaeological discoveries across India have been subjected to dating inconsistencies and politically influenced interpretations. In several cases, established dates have been challenged, altered, or dismissed not purely on scientific grounds but due to ideological pressures or institutional conservatism.

The archaeological discipline, which should ideally remain free from politics, has often found itself entangled in debates where science is overshadowed by competing cultural narratives. Such trends have created an atmosphere of uncertainty about the integrity of dating results, especially when broad civilizational questions hinge upon them. It is within this context that the dating of the Bakhshali manuscript must be viewed critically. The shift from 300 BCE to 800 CE is not a minor correction but a transformation of more than a millennium. Whether the early date was genuinely flawed or whether the later re-dating leaned toward excessive caution remains an open question. What is certain is that both dates cannot simultaneously be correct, and the current scholarly environment demands greater transparency and more rigorous methodology.

Given the manuscript’s global importance not only as an Indian document but as a cornerstone of world mathematical history its dating must be beyond dispute. For these reasons, I am requesting that the Government of India formally approach the British Library and the Bodleian Library to permit a fresh round of carbon dating under a joint scientific advisory committee. This committee must include experts in paleography, manuscript conservation, radiocarbon science, Indian mathematical history, and archaeological chronology. Only a fully transparent, multi-institutional, and peer-reviewed re-evaluation of the manuscript’s physical age can settle the debate. Such a request is not merely academic; it is a matter of preserving the authenticity of India’s scientific heritage. The Bakhshali manuscript is not only an artifact—it is an intellectual monument. It represents the brilliance of early Indian mathematicians who conceived, understood, and operationalized the symbol zero in ways that later transformed global science. To reconstruct the genuine history of ancient India, we must ensure that evidence of this magnitude is evaluated with utmost care, free from political influence, and grounded in the highest standards of scientific inquiry. A fresh dating of the manuscript is therefore not only justified but necessary. It is essential for restoring confidence in the chronology of India’s intellectual achievements and for presenting an accurate, scientifically validated narrative of the ancient past.